For our 2024 series of interviews, we wanted to hear from puzzle creators about their design process, with a focus on what they learned about making a specific puzzle. Read on for our interview with puzzle designer Vivien Ripoll.

Can you tell us a little about your background as a puzzle designer?

My name is Vivien Ripoll, and I’m a freelance puzzle designer. As far as I can remember, I’ve always been interested in solving puzzles (it’s probably the reason why I studied math, and most of my before-puzzle work was as a mathematician). Back in 2015 a colleague introduced me to Puzzled Pint (a monthly event with beginner-friendly puzzles), and I discovered with awe this type of mysterious puzzles where you have to somehow extract an answer, but with no explicit instructions, the first step being to figure out what to do. I l oved the intellectual challenge of those, a nd the sense of satisfaction of the ahas, and I quickly got hooked on puzzle hunt s.

I started designing puzzles as a hobby in 2016, for friends and colleagues. In t he summer of 2020, because of the lockdowns, a conference I was participating in ha d to switch to an online organization; I offered to create a custom o nline puzzle hunt, to replace the usual excursion of the conference. This was a fantastic experience, and the beginning of my career as a “professional” puzzle designer. Over t he last few years I’ve designed several custom puzzle hunts, mostly for online conferences and academic events. I also create puzzles for o ther types of events, such as interactive theater (last year for the Malden Mysteries, two puzzly pub crawls near Boston).

More locally to me, I desig n and organize custom escape room activities, or puzzly treasure hunts, for birthday parties and for school events. I have a special interest in the educational aspects of escape rooms and puzzles, and I’ve worked during one year at a primary school designing puzzles and escape-room-like activities adapted to the curriculu m.

My puzzle design is heavil y influenced by my education as a mathematician: I love interesting structures, geometric patterns, and some of my w ork is inspired by mathematical constructions. I also lov e playing with words and languages: b ecause of a weird life trajectory, I can now construct p uzzles in three languages (French is my mother tongue; most of my professional life has been in English; a nd I speak Spanish daily as I’ve been livin g in Mexico for six years now), and I sometimes have to deal with the complexity of translating/adapting a puzzle idea from one languag e to another.

Have you done EnigMarch before?

Yes! I learnt about EnigMarch back in February 2022 as I was lurking on the Discord of Escape This Podcast. I loved the idea and challenged myself to make a new puzzle every day in March. It was an amazing experience, both for meeting a great community of puzzle designers and puzzle enthusiasts, and also for the challenge of constrained creation, using the prompts. I learnt a lot about my creative process during this time, as I had to fight hard against my perfectionist side to be able to go quickly from an idea to a publishable puzzle. Here are my EnigMarch puzzles from 2022. I participated again in 2023, though not every day, for lack of time. I still managed to make 19 puzzles, and I was lucky to collaborate with other designers on two puzzles. Here are my EnigMarch puzzles from 2023.

Could you walk us through the design process of a specific puzzle you’ve made?

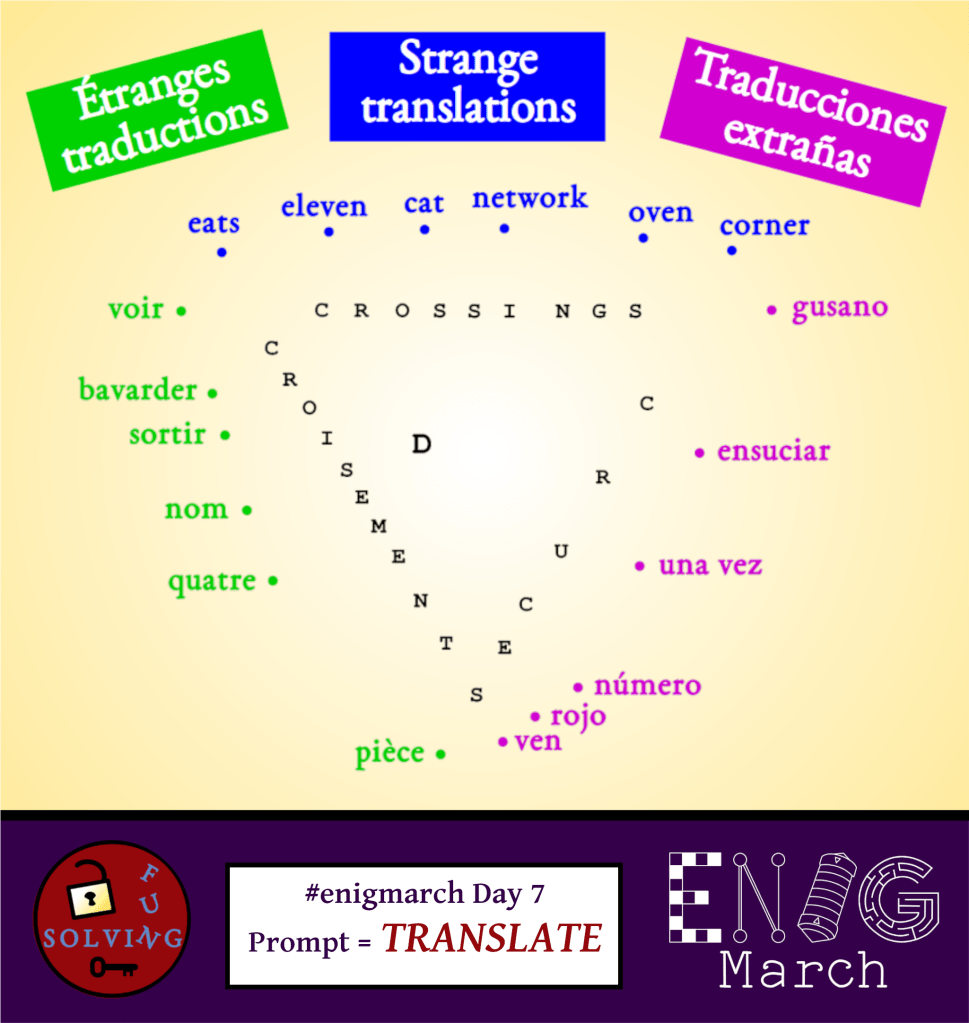

For EnigMarch, I usually try to alternate between puzzles in English, Spanish and French. But for Day 7 in 2022, the prompt was Translate, so it made me want to try a trilingual puzzle. You may want to try to solve it before continuing reading (obviously a lot of spoilers ahead!). Feel free to use a dictionary if you don’t speak one of the languages.

I chose to present this puzzle because it illustrates a few of my favorite things:

– using languages in an unusual way

– using a constrained geometric structure

– having part of the data also be the instructions

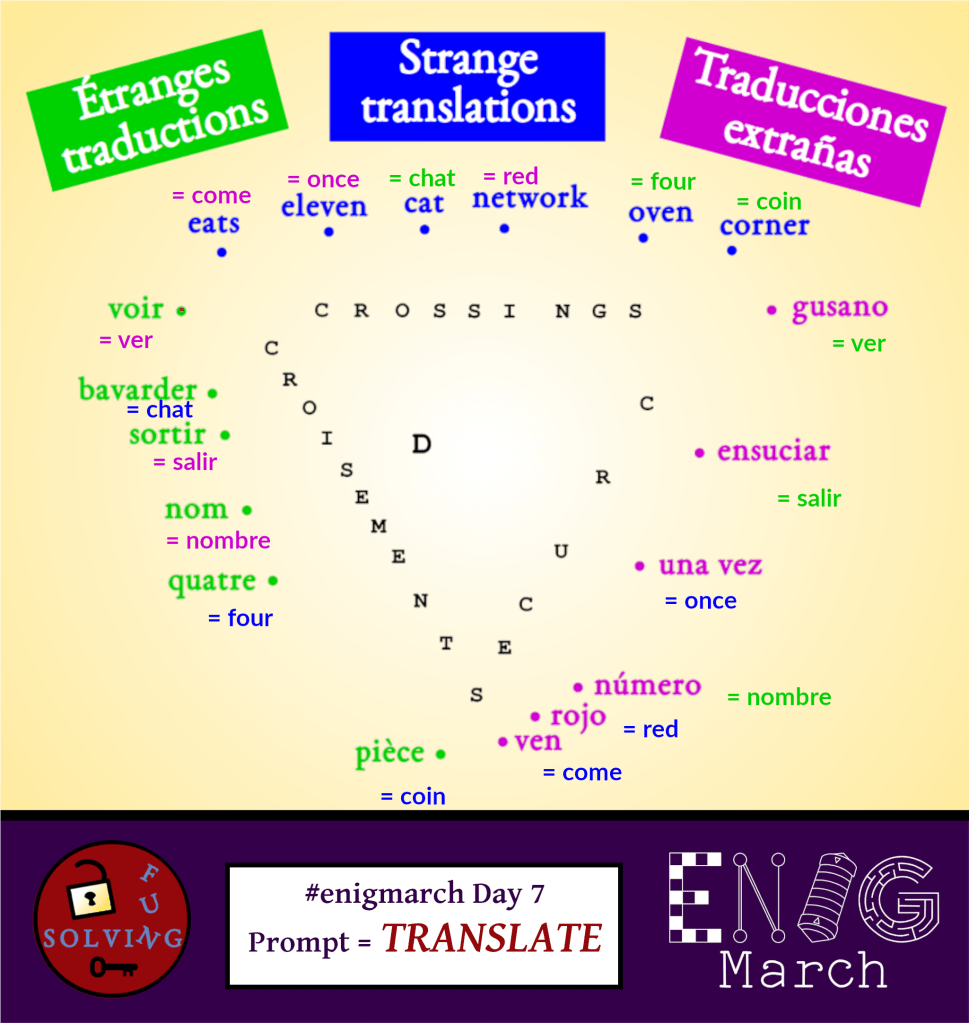

Solving process: We see the title in French/English/Spanish, and in the same color code, six words in each of the three languages (plus some dots and a bunch of letters in the center). The dots, and the word crossings, make the solver think they have to somehow connect the words. The theme being translation, we can try to translate a few of the words, but it doesn’t work directly. Though by translating a few words we might notice a strange thing: some translations give the same words! For example, cat in English translates to chat in French, whereas bavarder in French translates to chat in English. And this gimmick works for all the words, though you have to translate to the right language. Here are the translations:

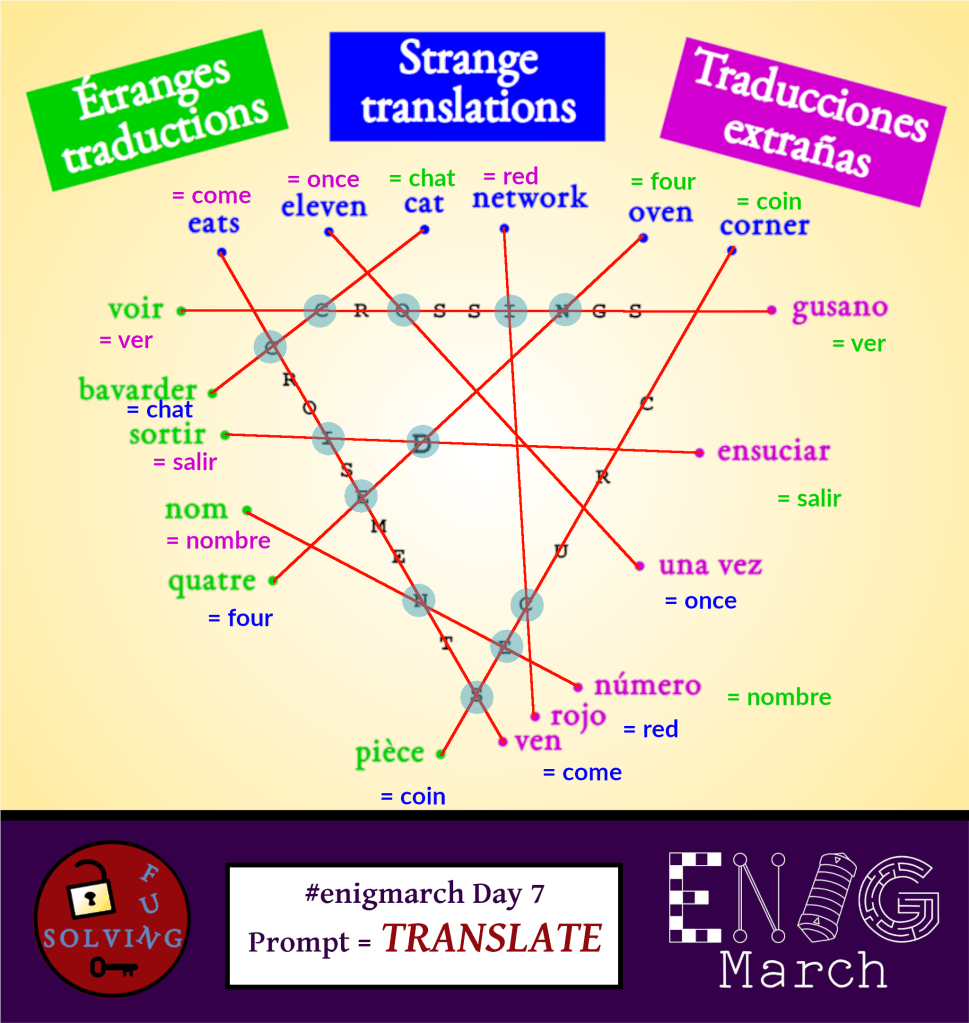

We now can naturally connect all the words two by two, using straight lines. And, given that the word written in the middle is crossings (and its translations), we look at the letters located at the crossings between two lines:

It gives the answer coincidences.

Design process: I had this idea of “weird translations” in my long list of unused ideas, so I already had several pairs of words that worked well. I revisited this list and selected three pairs for English-French, three for English-Spanish, and three for French-Spanish. Since it’s about pairings, it seemed natural to make a “pairing puzzle”, a classic form where you have to connect the pairs with straight lines (and, to get a final answer, you usually have a bunch of seemingly random letters in the center, and the ones that are not crossed out at the end spell the answer).

I knew I wanted to make the final answer coincidences, and I realized that I could get (almost) all the letters of that with the words crossings/croisements/cruces (I would only have the D to add). It felt great, because it meant I could put those words instead of random letters in the center, and in addition to being data used to extract the answer, those words would also be a clue (= look at the crossings of the lines).

I felt it would be nicer if all the words of the same language could be packed together, forming some kind of triangle. But then it was the beginning of a big headache because I had given myself many constraints:

– I wanted the words crossings/croisements/cruces on straight lines.

– From each language, I needed six lines starting there: three of them going to one side, three to the other side.

– I needed the lines to cross exactly at specific letters.

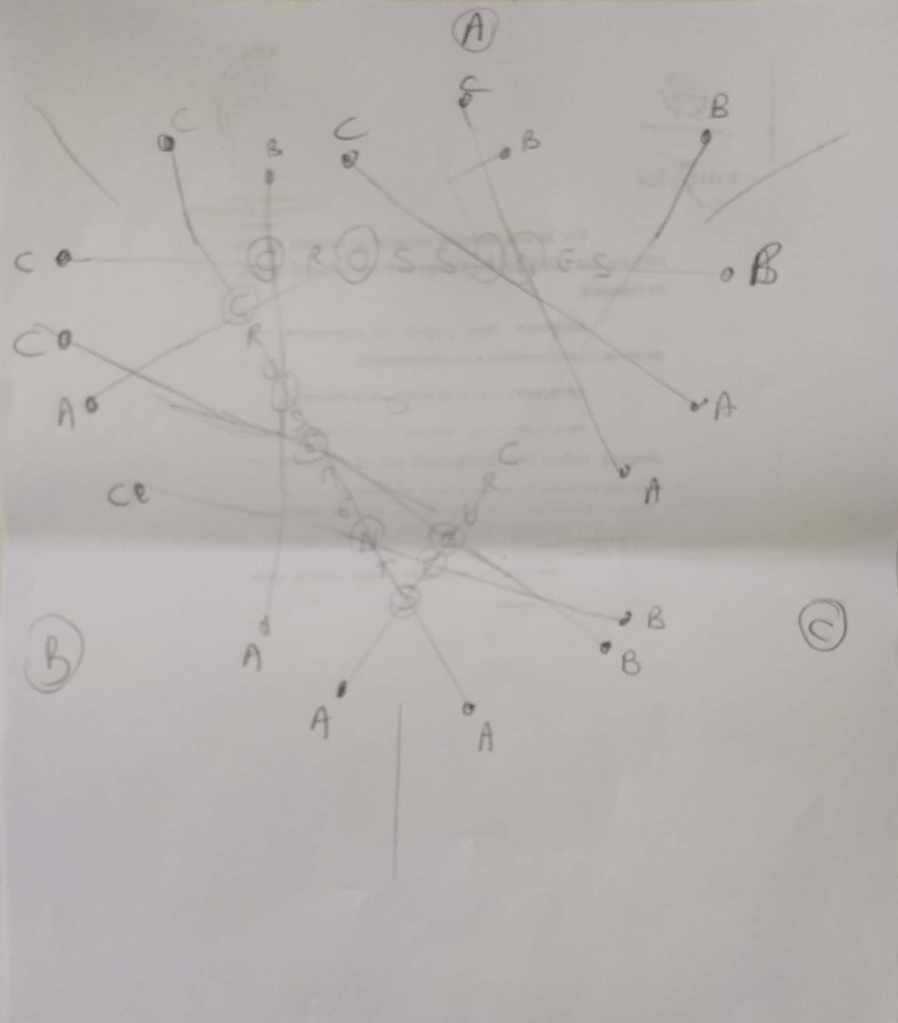

Making the construction work ended up being a puzzle itself (of the geometric/combinatorial type). Honestly I don’t remember how much time it took me, I think I did three or four hand-drawn drafts and a lot of head-scratching before getting something that more or less worked. Here’s a scan of the last draft, which I had used to make the final version.

This process illustrates something I’ve seen time and again in my experience: you have an idea, you combine it with another idea, you realize you can make it nicer by adding some constraints, but then you may have added too many constraints to be able to construct something that works, so you have to relax some of them, until you get something that is, hopefully, beautiful and solvable.

Do you have any advice or closing thoughts you want to leave people with about making puzzles?

Obviously, something that’s already been said several times, the first advice (as for any endeavour) is practice: solve a lot, design a lot. In more detail:

– Solve a lot, and after solving a puzzle, take the time to think about the process: What did you like/dislike about it, and why? What was fun, and why? Did it feel fair? What did the puzzle make you feel, and how did the puzzle manage that? Also, more technically, what are the “tricks” that the puzzle used to hide information?

– Design a lot: At first, don’t try to make a huge puzzle. Don’t try to make a hard puzzle (for someone not in your brain, it will be hard anyway!). Don’t try to make something completely new (yes, someone probably had this idea already; make your version!). And don’t try to make something perfect. Once you have an idea, make a draft right away, without taking too much time on the graphics, to be able to test the idea quickly with someone.

– Playtest: Try getting eyes on your puzzle as soon as possible. Test early, test often. I believe even the most experienced designers can have trouble predicting whether a puzzle idea will work or not. I’ve read somewhere this great analogy: when you design a puzzle, you are envisioning a path from the initial state of the puzzle to the solution. This path is like a trail in a dense forest. It is not obvious to find, but you want the solver to feel like it’s the right path, once they have found it. So you want it to be clearly the best path, among tens of trails they can explore at first. The issue is that, as the designer, you see the right path as obvious, so much so that you don’t notice most of the other paths. There comes the playtest, which allows you to check whether your perfect path is sufficiently clear, or if it needs more signposting.

– Get inspired: We don’t design puzzles in a vacuum. Take inspiration from what surrounds you, what you read, see, hear. We see patterns and structures everywhere, and you can make a puzzle idea out of almost anything. Have a file of notes easily available and take notes of any little idea. At the heart, it’s about finding interesting ways to hide information, and to leave just enough breadcrumbs so that the solver can understand how it is hidden. Also, take inspiration from other puzzles. It’s ok to make a new version of an old idea. I also often find ideas by using the wrong tracks I followed while trying to solve a puzzle.

– Use resources: nowadays there are many available resources online to help you create a puzzle. For example, if you are looking for a list of words that have a certain property, you often can find it using online tools (for example, Qat). More generally, there are many blog posts, YouTube videos, and a few books on puzzle design; the best link to give is a meta-link: this list of resources collected by Brett Kuehner (it is mostly focused on escape rooms, but there is also a big list of puzzle design links).

– Participate in EnigMarch! It’s a perfect way to hone your puzzle writing skills, and to have a great community see your puzzles!

Where can people find your work?

I regularly post new puzzles on my Facebook page Solving Fun, and my website is at https://solving-fun.com/. You can also find me as ViV in several puzzle-related or escape-room-related Discord servers.

Thank you to all the organizers of EnigMarch for making it such a puzzle feast!

P.S.: There’s a secret message hidden in the answer to the first question.